Elaine Jones received distinguished recognition by the Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment with a 2016 Visionary Award in June. The recipients of this annual award are selected for their “innovation, creativity, commitment to protecting the marine environment in environmental science, education, conservation or policy; engaged in projects involving public awareness, grassroots action or business and manufacturing practices.”

Jones has certainly demonstrated her worthiness for this award through her accomplishments from school teacher to education director of the Department of Marine Resources (since 1991), to lighthouse keeper of Burnt Island.

The Auburn native attended Hood College in Maryland as a biology major. In the summer of 1975, Jones, a sophomore participating in a work study program at the Aquaculture Center in St. Croix, USVI, had her first experience with marine science. Jones was fascinated by the ecosystems she explored. This experience changed her life's focus.

When the summer of 1976 came around, Jones missed her family and being in Maine. During her research to find somewhere in her home state to intern, she discovered DMR. After applying, she met with Director Ken Honey, who approved her for a position as a conservation aide working with staff monitoring heavy metal levels in marine mammals. The next two summer internships were spent with the public health division surveying what was going overboard. “We were referred to as 'sewer sniffers,'” Jones said laughing.

After graduation, Jones was a science teacher in the South Portland school system and still working at DMR summers.

Jones stepped out of the classroom and into the nursery, taking eight years off to raise her three children: Tamara, Gregory and Benjamin. When Ben was just 2, Elaine got “the” call. DMR Director Hal Winters was on the line. The agency's ed director, Lorraine Stubbs, was retiring — was she interested in the position?

“I had wanted to stay home one more year with my youngest, but I knew it was now or never. I said yes. I applied and was hired.” That was 1991.

One of the first things Jones did was to revamp the “Sea Comes to the Classroom” curriculum, which originally featured bringing a cooler of sea creatures to schools. As a one-time visit, it wasn’t an effective way to continue the program, so today schools across the state have 40-gallon tanks in their classroom due to Jones’ “Teach the Trainer,” a class required for all educators interested in incorporating the live education tool in their classrooms.

“I was transporting the animals to schools and the teachers weren't even staying in the classrooms,” said Jones. “I thought, if we're going to have a successful program, the teachers have to be trained to teach their students, and in turn, teach other teachers. It's the multiplier effect.”

But the teachers couldn't do it all so, Jones created a conservation program, Officer SALTY (Sea Animal Life for Tomorrow's Youth) taught by marine patrol officers. Officer SALTY would educate coastal youth about the ocean and about the anatomy and behaviors of marine life in the Gulf of Maine. DMR's education division set up 55-gallon saltwater tanks — acquired as part of an Outdoor Heritage Fund grant.

As the students and their teachers cared for the tanks, they learned about their important role as caregivers for the sea creatures living in them. An Officer SALTY went to these classrooms five times over a period of a few months teaching a four-section curriculum on ocean awareness, fisheries awareness, officer awareness and conservation awareness. Between the curriculum and caring for the sea animals, students learned about the importance of protecting and conserving the ocean and its resources.

In 1992-93, the new DMR laboratory was built. An aquarium was not part of the original plan.

“The people of Boothbay Harbor went to the commissioner with a request that the lab also include an aquarium,” recalled Jones. “Due to cost constrictions, only the outside shell for an aquarium was built. Deputy Commissioner Penn Estabrook told me I had to build the aquarium (the internal components) for DMR as the ed director — but there wasn't any funding in the budget. And, at that time I knew a little about aquariums from my summers working at DMR and knew there was one issue I had to tackle right away.”

Jones had to address the buildup of condensation on the windows of the exhibits due to the cold water temps. Windows had to be wiped off to see the fascinating creatures inside. In fact, paper towel holders were positioned near the tanks for visitors to use.

Jones visited the New England Aquarium in Boston where she heard about a man in Falmouth, Massachusetts who built tanks that were “glass clad” (a new technology — at the time — used by the airplane industry), which were 1-1/2” acrylic with 1/4” of glass on both sides of the viewing window. These were the tanks Jones chose for the new aquarium at DMR.

Between 1993 and 1995, Jones designed the aquarium and her husband Jeremy, a mechanical engineer, drew up the plans. Her design called for jagged walls with bumped out areas representing Maine's rocky coastline. DMR carpenter Tim Rand built the “rock” formations out of plywood. Jones' mason, Raoul Godin and his son, of Winterport, created walls to look like rocks out of stucco cement, Jones texturized them by making cracks in the cement with a screwdriver before it hardened. Another friend, Marc Godin (no relation to Raoul), came in and airbrushed and painted the rock.

The plumbing, aeration, chilling and filtering systems were built by staff of DMR's Maintenance & Operations staff. All the while, Jones was teaching courses statewide and using the tuition money to pay for the materials.

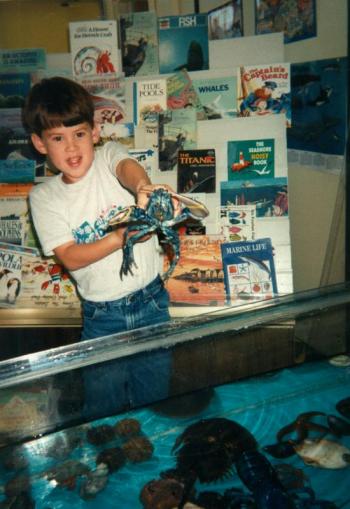

When it came time to decide what the exhibits would be, Jones put out a call to everyone she knew to help stock the exhibits — from fishermen/lobstermen to fish hatcheries. Jones lent fishermen large coolers to store the fish. The coolers were equipped with battery-powered air pumps. Every individual and facility responded to her call and on opening day, June 21, 1995, the aquarium at DMR had plentiful exhibits — alewives, herring, striped bass, flounder, salmon, lobster, mollusks and a variety of invertebrates (snails, octopus, starfish, sea urchins). Each year after the aquarium closes some specimens are wintered over in the wet lab, while others are given to classroom tanks and other aquariums.

“People have said it was the best aquarium because of all the hands-on opportunities with the 20-foot long invertebrates tank,” Jones said. “It's the personal touch of the staff being able to reach people one-on-one.”

During her career, Jones has established aquarium-based internships for students at the University of New England, University of Maine at Orono and Farmington campuses.

Jones is still quite passionate about the aquarium, the “Sea Comes to the Classroom” and Officer SALTY programs, and ... Burnt Island. Her name has become synonymous with the Burnt Island Light Station over the last couple of decades.

Burnt Island

In 1996, Jones was listening to a newscast announcement for the Maine Lights Program offering a transfer of ownership of Maine lighthouses from the U.S. Coast Guard. A telephone number was given in the broadcast and Jones called “right then and there.” She spoke with Peter Ralston at the Island Institute. Ralston was overseeing the transfers, and he encouraged her to go out and see Burnt Island.

“An island wasn't what I had in mind, but I took a skiff out there, out to the back side — there wasn't a dock then,” Jones said. “I looked. I fell in love. It had everything for educational purposes — a rocky shore, a beach, forest, meadow, seawall ...”

Again, DMR had no money to contribute to the maintenance, upkeep and any improvements once acquired. But Elaine Jones had been here before. “I thought it out. I made a list. I knew I needed to convince the commissioner that the island would advance the educational opportunities that could be offered by DMR,” Jones said. “And, I needed to start writing grants.”

And convince the commissioner she did. Grants came in from federal, state and local organizations, and there were donations from local businesses and individuals. Volunteers included everyone from the Boy Scouts to AmeriCorps, the Maine Conservation Corps, Landmark Volunteers, former lighthouse keepers and their family members, teachers, students, master gardeners … many, many people worked with Jones — always hands-on — worked her plan: to restore the keeper’s dwelling to be used in the living history tour.

The lives of Former lighthouse keeper Joseph Muise and his family became the basis for the script Jones wrote for the living history tour.

Jones learned there were four surviving Muise family members, who included Willard, the oldest son — living in Boothbay Harbor — who shared his memories of the island. His three sisters came back to Burnt Island in 1999 and shared more of the stories that are interpreted today. The living history tours that began June 30, 2003 — just 10 days after the grand opening of the restored keeper’s house — to the way it was in 1950. The tour also includes information about Maine's fisheries, a walk and talk about the five acres island's geography and vegetation.

But Jones' vision for Burnt Island went beyond the living history tour. She designed the island's Education Center to resemble a lifesaving station with a first floor classroom, kitchen, restrooms and showers and storage; the upstairs loft provided sleeping bunks constructed to resemble berths on a ship. This facility was to be, and has been, used for educational programming for school children from as far away as Aroostook County — including three-day programs and summer camps, for teachers interested in bringing their students to the island, and for use for teachers participating in re-certification and continuing education courses written by Jones.

“This is a well-deserved award for Elaine,” said Maine DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher at the June event. “She is a visionary leader for Maine students, educators and residents, guiding and supporting their appreciation of Maine’s marine environment.”

Jones gratefully acknowledges all of the support she's received from local fishermen over the years, such as Clive Farrin, stopping by the island when a school group was there to teach the kids about lobstering, and Rusty Court and others who respond to her calls for help for whatever needs doing and continue to do so today.

“I credit the community, local businesses, staff — here at DMR and on the island — Howard Wright, Jean McKay and the Keepers of Burnt Island Light (a nonprofit organized to oversee the tours and work needed on the island), the countless volunteers, and the schools, teachers and kids, who have supported the programming on Burnt Island,” Jones said. “It's about the positive connections that are made. This is their island. This is the people’s island.

“I think I've made a difference — in the classroom, at the aquarium, and on Burnt Island. What more could I ask for?”